Coming full circle

When Luís Carvajal-Carmona left his Colombian village to study in London and Oxford, he didn’t suspect that clues to some of the world’s most vexing health problems had surrounded him all along.

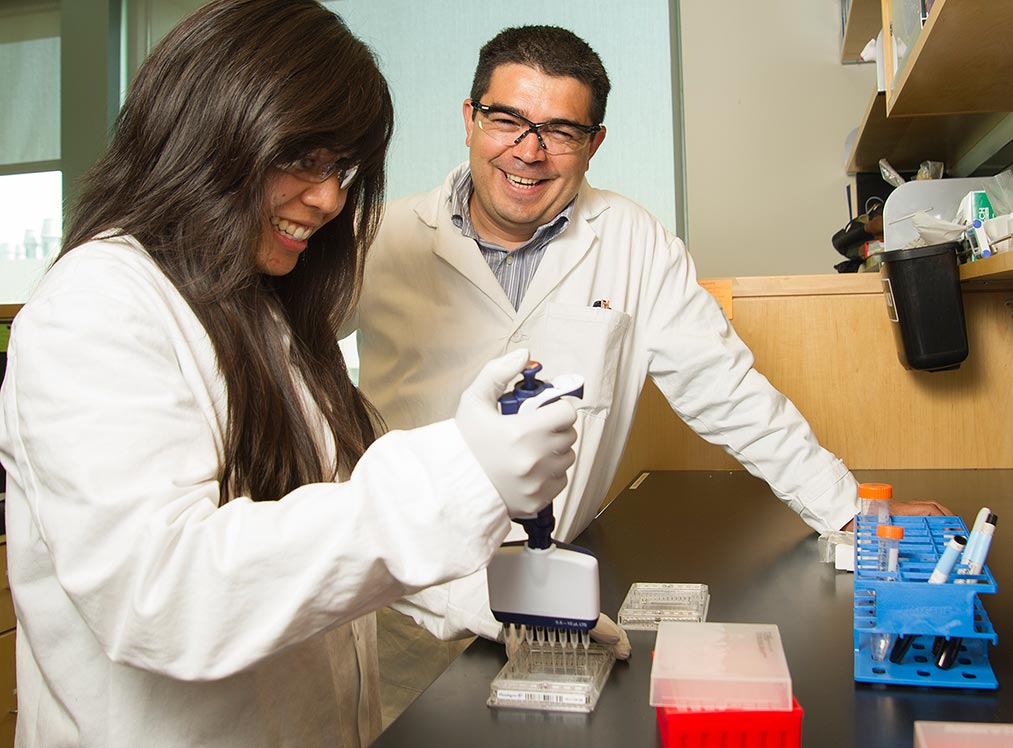

Today, the assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular medicine’s studies of the genetic make-up of Andean villagers is revealing interesting details on their history and ancestry, and contributing to the rich body of important research on genetic diseases, especially cancer.

“In remote regions of the Andes, people have been relatively isolated for more than 500 years,” he says. “This, combined with some intermarriage and large families, makes them genetically more similar than populations almost anywhere else in the world — and a gold mine for research.”

His work to find mutations passed down by village ancestors that will likely lead to cancer has led to screening of 191 women with breast cancer in Colombia and identification of 19 patients and families with the same genetic mutation in the BCRA1 gene.

“If we studied 1,000 unselected European-American women, I can almost guarantee you that we would not find even two patients with the same mutation. This genetic homogeneity will lead to easier identification of new cancer genes, and we are optimistic that this work can rapidly contribute to better personalized medicine and global cancer health.”

At the UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center, he is working with oncologist Helen Chew to analyze the genomes of about 400 breast cancer patients treated with drugs that can cause debilitating muscle pain, hoping to identify genes associated with this toxicity and tailor treatment more effectively.

Glenda Drew wears her heart on her arm — literally.